I Speak, Therefore I Am.

A multilingual identity crisis, but make it philosophical.

Leon Tolstoy once critiqued art that is disconnected from the common experiences and feelings of people, suggesting that such art struggles to communicate effectively. Art, in his view, only truly resonates when it is rooted in shared cultural understanding

"Art is a human activity consisting in this, that one man consciously, by means of certain external signs, hands on to others feelings he has lived through, and that others are infected by these feelings and also experience them" (Tolstoy, What is Art?).

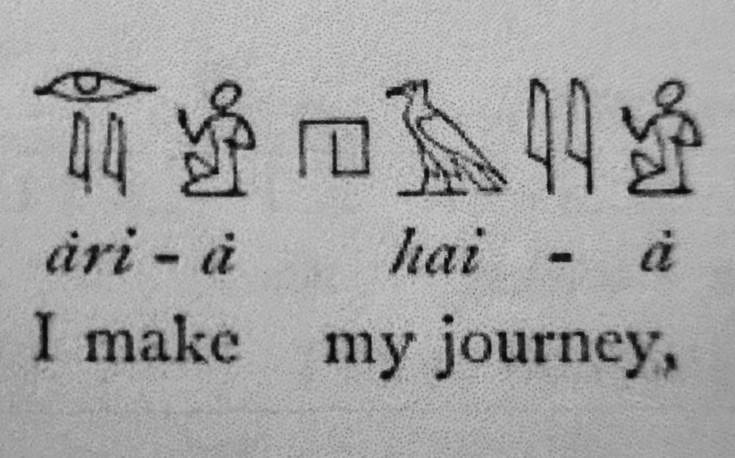

In that sense, art is inseparable from language: it is the vessel through which culture, emotion, and thought are transmitted.

I’ve often noticed the same principle in language itself. Expressing thoughts in English, for instance, can feel lighter, almost freeing the words from the weight of vulnerability that my mother tongue carries. In contrast, translating a French joke can be a delicate act since the humor often disappears, or worse, becomes something else entirely.

Spanish, while bewildering in its adjectives and gendered constructions, has a familiar rhythm across Latin-based languages. There’s a structure beneath the surface that, once understood, makes the language feel less foreign and more intuitive.

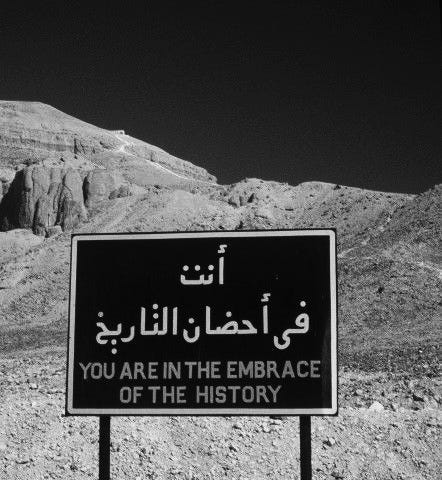

A tiny slip in Arabic, whether a haraka (short vowel) or a tense, can completely change the meaning of a sentence. It’s a language that demands patience, because words can just as easily break as they can heal.

I apprehend that language ought to serve for communication however, it plays a crucial role in thought and culture perse. When experimenting with multilingual puns, I might be enjoying a joke but I am first and foremost, glimpsing at how a culture thinks.

Saying “the vase fell” versus “I made the vase fall” reflects beyond grammar because it uncovers underlying cultural attitudes toward responsibility.

Language molds identity, and by gathering several, we become living amalgams of cultures, each shaping how we feel, think, express ourselves and how we see the world.

In English, saying “I’m sorry” often directs attention outward, toward the person you’ve wronged—which could be perceived as transactional in one way or another.

In French, “Je regrette” shifts the focus inward: it’s a statement of personal feeling, an admission of remorse without necessarily addressing the other person directly.

Spanish blends the two: “Lo siento” literally means “I feel it,” carrying both the weight of internal emotion and empathy toward the other. In Arabic “أعتذر” (aʿtadhir) conveys a sense of seeking forgiveness. Apologies in Arabic revolve around an acknowledgment of wrongdoing and a sincere request for pardon.

In French and Spanish, one “takes” a decision; “prendre une décision” or “tomar una decisión”, as if you’d reach out to grasp something already expecting to be claimed.

In English, we “make” decisions, creating them as if from raw material, fulfilling the philosophical doctrine of authorship.

In German, one “trifft eine Entscheidung”, literally “hits” or “meets” a decision—implying a confrontation, embodying the principle of cause and effect, as though every choice, nolens volens, strikes its consequence.

Meanwhile, in Russian, you “accept” a decision; “принять решение” (prinyat’ reshenie), insinuating surrender to fate.

Each verb reflects a profound philosophy: whether we seize, build, collide with, or yield to our choices.

These derisory differences can potentially reveal how each culture perceives responsibility, emotion, and social connection including the unspoken rules that govern human interactions.

Speaking of which, language also plays a fascinating role in shaping perceptions of gender.

In Arabic, رجل (rajul, “man”) and امرأة (imra’ah, “woman”), which are the roots of adjectives often associated with masculinity and femininity, like الرجولة (al-rujūlah) and المروءة (al-marū’ah). Many people mistakenly treat these traits as exclusively male or female, but their etymology reveals a more universal meaning.

الرجولة (al-rujūlah) comes from رجل (foot / “man”) and originally describes someone who stands firmly on both feet—a responsible, reliable individual rather than a purely masculine quality.

Likewise, المروءة (al-marū’ah) denotes a right-doer, a generous and ethical person, and is not tied to gender. This means it is entirely correct, and meaningful, to say رجل ذو مروءة (rajul dhū marū’ah) for “a man of integrity” or امرأة ذو رجولة (imra’ah dhū rujūlah) for “a woman of steadfastness.”

Arabic, in this way, emphasizes that virtues such as integrity, responsibility, and generosity transcend gender, even if common usage sometimes obscures this universality.

Just as art fails when detached from shared experience, language loses its depth when divorced from culture.

Every word is a vessel of collective memory, emotion, and identity. Mastering multiple languages doesn’t just make one a communicator more than it makes one an observer, a translator of both words and worlds.

“Learning another language is like becoming another person.” —Haruki Murakami

Art and language alike demand empathy, open-mindedness, cultural awareness, and the willingness to inhabit someone else’s thought-space.

Tolstoy would also remind us that the art of communication –whether through painting, music, or words– is only as good as the connection it creates.

And perhaps, just perhaps, the more languages we speak, the more connections we can forge, not just with others, but with ourselves…

© 2025 ashndust. All rights reserved.

This was a really cool read! I'm a bilingual speaker (native English speaker and fluent in urdu), I'd love to be able to write stuff in Urdu too because sometimes English just doesn't do justice to the complexity of Urdu. What languages do you speak?

I'm leaning Hebrew, Vietnamesse,Thai, Japanese, Arab, German, Portuguese, Korean, Russian, Tukish, French, Italian, Swedish, Norwegian, Chinese (since 2019 by myself) and English (always reinforcing)