War Internalized, Nonchalance Romanticized.

On how humanity’s evolutionary and historical conflicts shape the paradox of modern self-discipline.

I’m assuming 1912 rings a bell, and 1945 opened the door to today's misery.

Perhaps we’re enduring a third chaos, a tacit one, as if agony hasn’t lasted for as long as man has existed.

Yes, “man”…

How egocentric of me to sigh as I speak of my own species, but shouldn’t I wear that belonging with pride?

After all, I proudly associate myself with Homo sapiens, chasing the mantle of Homo Deus, aching for unattainable perfection.

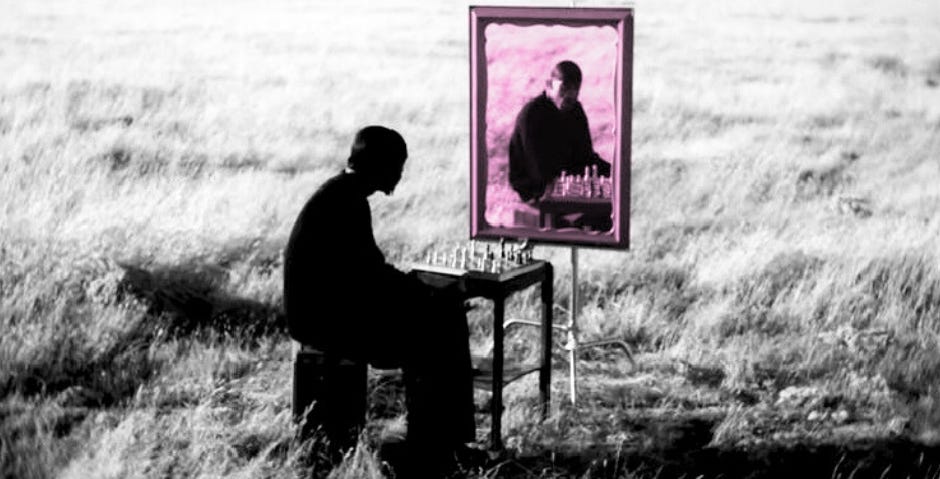

But maybe it’s our brokenness that keeps birthing conflict, ranging from the wars with missiles and trenches to the invisible ones. The ones with no anthems, no medals, no ceasefires. Just you, who you were and who you ought to be.

What if perfectionism is just pity for the broken parts of yourself?

I’m not here to wrap this in colorful optimism—too much has been left unsaid because silence feels safer. But the toughest battles don’t involve gratuitous gore or gunshots; they unfold in hushed self-destruction and behind an immutable, deadpan countenance that time has etched onto a warrior’s face.

How hypocritical (or rather, how dissonant) of us to seek peace and despise war when we are wired for both.

Like it or lump it, conflict runs deep in our evolutionary code, whereupon the biological mechanisms that once ensured survival are repurposed within modern systems and rendered socially palatable rather than eradicated. Which brings me to wonder whether Cain and Abel’s vestiges ever faded, or whether they evolved to fit the 21st century’s view of aestheticism, incorporating themselves into systems that incarnate pseudo-discipline, taking shelter in self-improvement’s name all while concealing the maladaptiveness they perpetuate.

This isn’t about defending war nor idolizing peace, as though either could be isolated into something absolute. Sometimes war becomes a condition we inhabit so thoroughly that it ceases to feel external and turns into a subconscious ache—not out of malice, but conditioning familiarity. Perhaps an excessive amalgam of strict order and enforced coherence might cultivate a yearning for chaos. Or it could be that this longing is not for destruction itself, but for its intensity; the process of seeking something that ruptures the numb equilibrium we are taught to call stability.

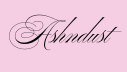

It may be that the most sobering truth lies in how selectively we have trained ourselves to feel. We have grown accustomed to missiles but not to emotion; to airstrikes absorbed with the same passive detached expectancy as weather forecasts. Violence, when mediated and distant, becomes somewhat legible while emotion, by contrast, is deemed unruly and excessive. It is often framed as a threat to composure and as irrationality’s ally, when in truth it is the act of caging those emotions that creates the very aftermath we fear.

We now inhabit a world in which shedding tears is perceived as more raw and more vulnerable than death per se. Death has been rendered statistical and digestible, timelessly molded to fit attention-grabbing, often lucrative headlines, whereas emotion plays the anti-conformist intruder in the parody. And so we learn to endure catastrophe with restraint: we have become accustomed to intellectualizing suffering, to romanticizing self-sabotage by disciplining ourselves against feeling too much (or just feeling in general)—mistaking numbness for resilience, and trading our perception of control for illusory moral clarity

In a world where all lives are declared to matter, some lives are more equal than others since apparently, hierarchy persists even in death. Some corpses make headlines, converted into epics, conveniently narrated for collective consumption. Others are reduced to trends, fugacious spectacles, measurable through none but fleeting and exiguous attention spans. Some are buried in silence, excluded from public recognition. And some are not buried at all…

This inequity is not merely external. Perhaps it reflects an internalized condition: the parts of ourselves we neglect, ignore, and often refuse to mourn.

Maybe that’s you—the corpse rotting in the back of your mind.

In the same way that society parses death into legible categories, we fragment our own consciousness by categorizing emotional experience into compartments of tolerable affect; the socially acceptable emotions we are allowed to express. And the forbidden affect, which takes shape in socially unacceptable emotions such as rage, fear, and grief, etc. In doing so, we self-censor our emotional reality to fit internal and societal expectations, romanticizing nonchalance as poise and sophistication while whatever remains outside these partitions festers, forging unresolved trauma. It may be invisible to both the surrounding world and the self, yet its effects are unavoidable—they shape the trajectory of our interior life as inevitably as any historical catastrophe shapes the world, in accordance with the butterfly effect.

Just as wars, revolutions, and disasters reshape societies, our internal conflicts reshape our consciousness. The microcosm of the mind never ceases to reflect the macrocosm of humankind’s history.

© 2026 ashndust. All rights reserved.

Incredibly well written dissection of human consciousness. Appreciate the layering of perspectives without judgement. Followed immediately.

mind: blown. What an incredibly perceptive and well-thought out piece. Love it!!